Redistricting 101

What is Redistricting?

Redistricting is the process of redrawing the lines of legislative districts to ensure equal and equitable political representation of residents. This process usually occurs once every decade in the year following the decennial census and affects political districts at the federal (congressional districts), state (assembly and senate districts), and local levels (county supervisorial, city council, school board, and special districts).

Why does redistricting matter for the equity movement?

For generations, redistricting has been used as a tool to disenfranchise and dilute the political power of communities, particularly communities of color. Redistricting has been weaponized and used to strengthen white political power and disadvantage communities of color by denying those communities the ability to have fair political representation. Such representation is only possible if voters have a fair opportunity to elect candidates of their choice, which is largely dependent on how legislative districts are drawn. As legal scholar Justin Levitt notes, “[t]he way that district lines are drawn puts voters together in a group . . . Depending on which voters are bundled together in a district, the district lines can make it much easier or much harder to elect any given representative, or to elect a representative responsive to any given community. And together, the district lines have the potential to change the composition of the legislative delegation as a whole.” Historically, voters of color and other marginalized communities have been intentionally “bundled” into districts in ways that dilute their potential voting power.

Gerrymandering: Taking your power

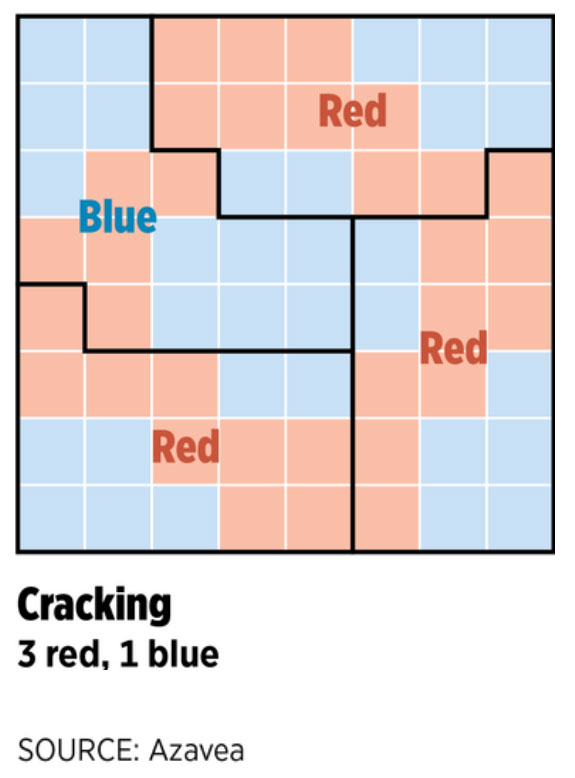

The primary method used to dilute a community’s voting power through redistricting is called gerrymandering, which generally refers to the practice of drawing legislative districts in ways that give an unfair advantage to a particular group (e.g., a political party or racial/ethnic group). There are various gerrymandering tactics, with two of the most common being referred to as “cracking” and “packing.”

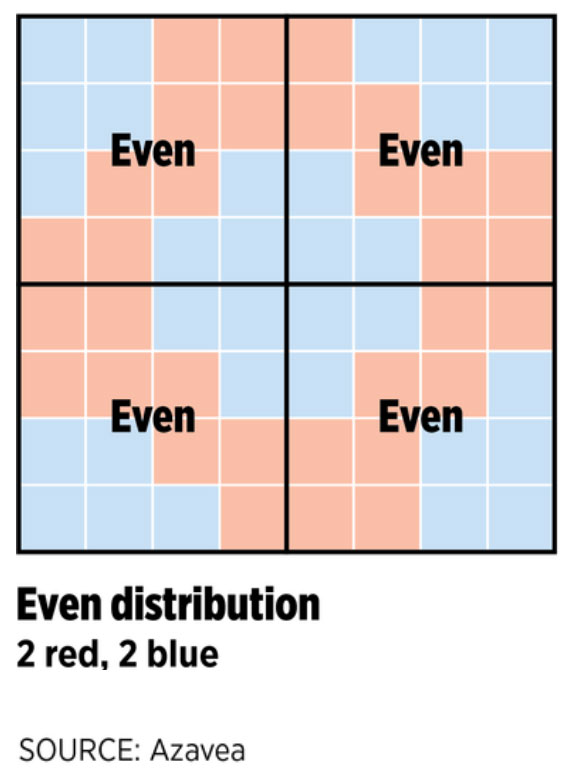

Even Distribution

With an even distribution, each district is divided such that the overall population is evenly distributed over all districts.

Cracking

Cracking is the practice of splitting like-minded or potentially like-minded voters across many districts, thus weakening their impact by ensuring that no particular district has a sufficient number of those voters.

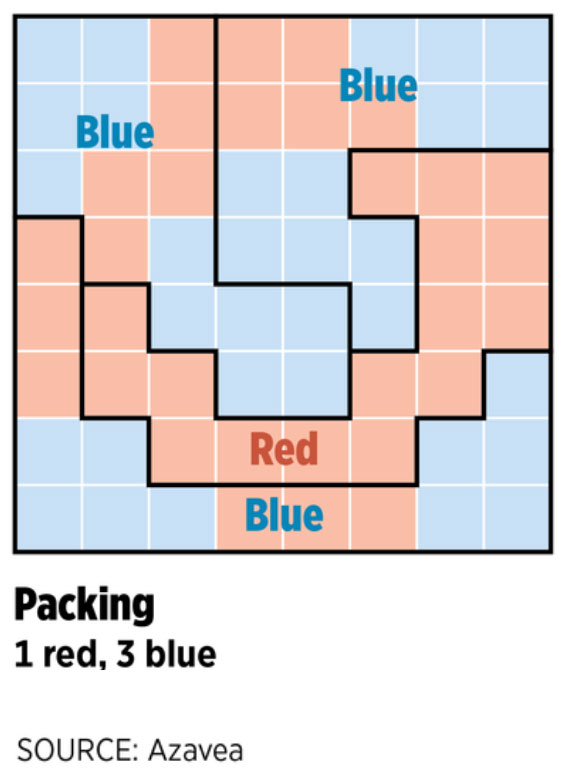

Packing

Packing is the practice of concentrating like-minded or potentially like-minded voters into one district or a few districts. While packing does give those voters power in their respective district(s), it weakens their overall impact on a legislative delegation as a whole. For example, in a jurisdiction with five city council districts, a group of voters that could otherwise be sufficiently large enough to be fairly bundled with other voters across three districts may be packed in unfairly large numbers into just two districts, thus limiting that group’s overall impact on the city council.

The People’s Input

While attempts to dilute the voting power of people of color and other marginalized groups through gerrymandering have become less egregious over time, there are still attempts to do so at all levels of government. Additionally, it is possible for gerrymandering to occur inadvertently. Whether intentional or not, there are ways for redistricting to be used to disempower traditionally and currently marginalized communities. For this reason, those communities must be vigilant and involved in the redistricting process.

Redistricting FAQs

Get answers to the most common questions about redistricting in California at all levels.

What are independent redistricting commissions?

Independent redistricting commissions (IRCs) comprise citizens who are neither legislators nor public officials and are mandated to create maps for their jurisdiction that comply with federal, state, and local laws. IRCs redraw districts through a transparent deliberation process that requires public engagement and encourages public input.

How are lines decided?

Using data from the 2020 Census, the California and Los Angeles CRCs must draw lines for

single-member districts that comply with the following redistricting criteria:

- District of equal population, which means that each district will have a reasonable equality of total population within its boundaries;

- Adherence to the federal Voting Rights Act, which prohibits the dilution of the voting

power of racial, ethnic, and language minorities;

- Geographic contiguity, which refers to the requirement that a jurisdiction is not interrupted by another land or a body of water (unless connected by a bridge, tunnel, or ferry);

- Geographic integrity, which refers to the requirement that counties, cities, neighborhoods, and communities of interest must be kept whole so long as doing so does not violate any of the three criteria just mentioned;

- Geographical compactness, which refers to the requirement that the commission must not bypass nearby communities for more distant ones; and

- Nested districts: the California CRC must also comply with the nested districts requirement, which mandates that “each Senate district shall be comprised of two whole, complete, and adjacent Assembly districts, and each Board of Equalization district shall be comprised of 10 whole, complete, and adjacent Senate districts” (CA Const., art. XXI, § 2, subd. (d6)).

How are incarcerated included in the redistricting process?

At the local level, incarcerated people must be counted in their home communities, rather than at the stated correctional facilities where they are detained. At the state level, in January 2021, the CRC approved a similar requirement.

What are the protections provided by the Voting Rights Act?

The federal Voting Rights Act of 1965 prohibits discriminatory systems and practices that would prevent a voter from casting a ballot for their candidate of choice. This includes drawing of maps that would dilute the voting power of minority groups. This has historically been through “packing” (concentrating as many people as possible from one minority group into one district) and “cracking” (splitting a minority groups across different districts) all with the end goal of minority vote dilution.

What is a community of interest and what should that matter to me?

State law defines a community of interest (COI) as a “contiguous population that shares common social and economic interests that should be included within a single district for purposes of its effective and fair representation.” This does not include “relationships with political parties, incumbents, or political candidates.” The commission is mandated to keep communities of interest whole because those communities likely constitute a voting bloc with similar representation needs and preferences. Breaking up COIs would result in weakening their voting power and ability to elect their candidate of choice. Commissions do not necessarily know which particular COIs exist within their jurisdiction(s) and, therefore, rely heavily on the public to provide this information. Without your voice, the commissions will be unaware of your policy preferences and characteristics. This means your community might be drawn within the same district as a neighborhood that does not face the same challenges as yours.

Who should I think about when describing my community of interest?

Folks who are in the same struggle, impacted by the same conditions as me: pollution hazards, lack of access to healthcare, food deserts, police violence, poverty, lack of parks/open space, under-resourced neighborhoods, etc.

Folks who share similar backgrounds and identities with me: farm workers, working class, parents, people of color, low income communities, immigrant communities, LGBTQ+, indigenous communities, etc.

Folks who share similar values and care for the same issues as I do: healthcare as a human right, rent control, more schools not prison, police accountability, Black Lives Matter, immigrant rights, etc.

How can I participate?

The main goal of participation should be for community residents to inform the commission about their COIs and ensure that the commission draws lines that respect how people understand the boundaries of their COIs. To achieve this, CBOs should help residents identify their COIs, draft COI maps for submission to the commissions, send letters, and provide public comment during community hearings. When we draw the map, we choose what hospitals, schools and resources are funded in our neighborhood. By joining together to speak out for fair districting, we can make our communities whole and deliver what our schools and families need for a decade to come.